Amado M. Mendoza, Jr.

Department of Political Science

University of the Philippines (Diliman)

E-mail: ammendozajr@gmail.com

Democracy is the most difficult socio-political regime. It requires a critical mass of economically-independent citizens imbued with adequate intelligence and a healthy civic spirit to get engaged in public matters. Democracy demands a lot both from the governors and the governed. Authoritarianism does not. Democracy offers the possibility of a progressive empowerment of citizens. However, the process is not automatic or natural. The true sovereigns, the people, citizens and all in the body politic, must empower itself even as it is mindful of its public duties and responsibilities. After all, the default behavior of all if not most political leaders in any political regime is to fear and prevent the growth of an empowered citizenry.

The health and quality of a democracy depends on its capacity to unify a people divided regularly by elections. That used to be the strength of the US. No longer true since the election of Obama. Now, Donald J. Trump is president only of his political base like Rodrigo R. Duterte in the Philippines.

Unification after elections is achieved if the ruling government, together with its partisans, respects, defends, and promotes the legitimate interests of electoral minorities and political opposition. The primary obligation of all is to pay taxes and uphold the law. Both chief executives revel at savaging political opponents and tilting against enemies and social ills (real and imagined), to catcalls, cheers and the great delight of their partisans. Trump seems to be at war with his own Republican party.

US President Donald Trump enjoying a media moment with North Korean leader Kim Jung-un in Sigapore

Duterte did Trump one better recently and has upped the ante by repeatedly attacking the Catholic Church, its clergy, and even Jesus Christ and His teachings. Earlier, he declared that the Philippine Constitution is just a piece of paper and that he is not bound by it. In fact, he argued that the basic law of the land was being used by his political enemies to frustrate his ‘Change is Coming’ programme—a mishmash of promises and motherhood statements. Instead of being appalled by an apparent volte-face from his oath of office, Duterte is cheered on by his followers who seems amenable to the establishment of a nebulous ‘RevGov’ or revolutionary government. Instead of being impeached for culpable violation of the Constitution, a pliant legislature initiated impeachment proceedings against one of his most prominent critics instead. Instead of arresting him, the Philippine National Police (PNP) recently declared that his will is the law.

On the whole, both presidents are the latest exemplars of uncivil demagoguery and uncouth thuggery, though Trump seem to be copying from Duterte’s playbook. Notwithstanding their departures from usual norms of civility and public conduct, both conduct themselves with great confidence buoyed by the support of subservient political lieutenants, legislators, judges, bureaucrats, and their defined political bases.

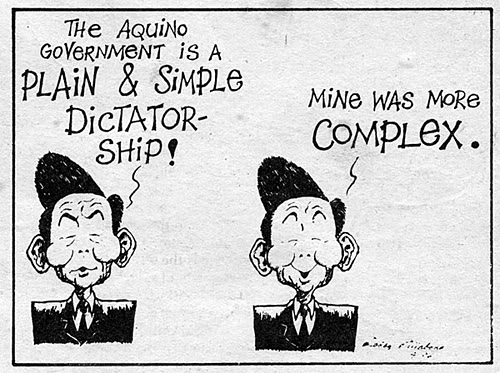

A number of my colleagues at the University of the Philippines Department of Political Science and College of Social Science and Philosophy had strongly suggested that it would be better for all if we stopped calling the socio-political system in the Philippines a democracy but label it instead as an electoral oligarchy–a political system ruled by a faction of the political-economic elites by voters in regular elections both at the local and national levels.

They make a very strong case. While indeed elections had been and being are mounted regularly (at least, after 1986 to present day; and between 1946 and 1972), the first test of being fair and fraud-free has not been met repeatedly. For this reason, losing candidates almost always claim that they had been cheated rather than bested in a fair electoral contest. In many parts of the country, dependent voters either sell their votes or are cowed to vote according to the preferences of local strong men. Anecdotal evidence suggest that in Muslim Mindanao, ballots are pre-accomplished and pre-counted inside municipal halls and police/military camps while voters innocently cast their votes in full-view and duly recorded by national mass media. Entry into the candidates’ pool is restricted by laws banning supposedly nuisance candidates—laws which effectively bar less prosperous and less-connected citizens from running for public office.

Philippine Congress hears President Aquino’s SONA

Secondly, virtually the same political families and clans have dominated Philippine politics since elections had been instituted by the American colonial authorities at the beginning of the 20th century as an anti-insurgency and anti-revolutionary strategy–that is to divide the Filipinos who wanted to complete the Philippine Revolution and establish an independent Philippine nation-state. When outsiders from the under-classes managed to win electoral posts, the ruling oligarchy decided to kick them out of office by branding them as subversives. If there were new entrants into the ruling circles at both the local and national levels, they are immediately socialized into the dominant political culture, the elements of which include these truisms: the public treasury is a private trough for politicians and other public servants! And that one must be smart and fast enough to figure out how to get the most of it while in power. It is never too early to prepare for re-election so good times will never end! Political support is gained through the grant of special and divisible favors and goodies to supporters, backers, and financiers. After all, we are above the law. We are in fact the law. We execute what we declare is law; we legislate; we interpret what is lawful; and we enforce the law!

Lastly, the country’s political system is hobbled by a flawed system design. Marrying a multi-party system (which the political science literature finds to be best paired with a parliamentary system) with a presidential system, all chief executives since President Corazon C. Aquino (1986-1992) are minority presidents. Notwithstanding the wisdom of having second round run-off elections, the country’s political leaders argued against the exercise deeming it to be too expensive and divisive (!). Furthermore, the single presidential term limit had the unintended consequence of weakening already feeble political parties. The outgoing president, nominally the leader of a ruling party, is reduced to being a lame-duck and cannot impose discipline. In many instances, ambitious politicians who were unable to win their political parties’ nod found it easy to bolt and form new parties behind their candidacies. In this respect, political parties remain candidate- centered rather than programmatic and served mainly as vehicles for the political ambitions of clan-supported politicians who, once in office, will rewards family, friends, supporters and financiers with political posts, juicy government contracts, and/or policy favors and preferential treatment.

To be continued…