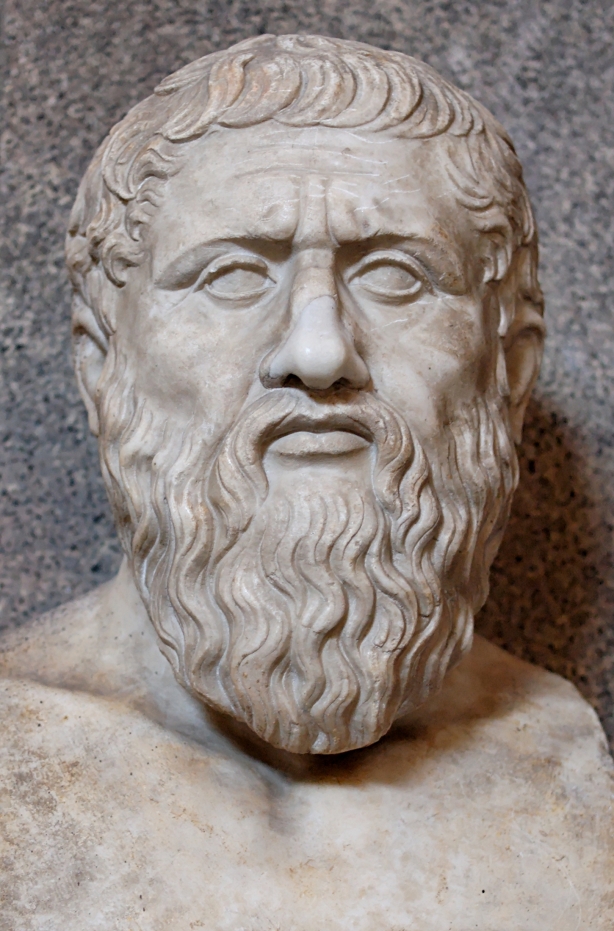

The concern with political elites and political leadership is as old as political philosophy. Ancients such as Plato grappled with the question—who should rule? And as early as Plato’s time, several verities about ruling and leadership have been arrived at:

- Not everybody can rule.

- Mob rule is no rule at all.

- Some must govern all others because they are fit to rule.

That these points were established during the heyday of Athenian democracy raises not only ironies but several interesting philosophical, theoretical, and pragmatic puzzles. The encounter between democracy and elite rule will exercise many philosophers and theorists cognizant of the antimonies and possibilities engendered by such a mating. In political philosophy and theory, the place of the elite and their right (and obligation) to rule has been well argued. Plato’s “philosopher-king”, Aristotle’s “exceptional man”, Machiavelli’s “prinsipi“, Hobbes’ “Leviathan”, Nietzsche’s “uber-man”, and Lenin’s “proletarian vanguard” were all variants of the same theme—the best man (men) should rule because they are the best. The corollary question—why should we obey?—was answered in a similar manner. We must obey our leaders because they are the best among us.

Of course, there was a time in man’s history that the rule of rulers was justified in other ways. They all fall under the rubric “divine right theory of kingship” and have been formulated in three variants:

- The ruler has received a direct mandate to rule from God.

- The ruler was a descendant of God.

- The ruler was God!

In the Celestial Kingdom, when a ruling dynasty is overthrown or deposed and a new one takes over, the deposed emperor supposedly lost the mandate of the Heavens. Japanese emperors up to Hirohito claimed lineage to the Japanese sun goddess, Amaterasu while Ethiopian emperors up to Haile Sellasie similarly claimed King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba as their ancestors.

Save for Niccolo Machiavelli’s prince, none bothered to theorize on elite rule until Hobbes’ Leviathan. After Hobbes, democratic theory made substantial progress with the work of Locke and Rousseau. But the antimonies between elitism and democracy were apparent even in Rousseau. While he acknowledged the sovereignty of the body politic, expressed as the General Will, Rousseau lamented that only the one who knew but had not directly experienced all of the human passions can be the law giver/maker. Earlier, despite his republican inclinations, Machiavelli likewise extolled the virtues of God-like men, e.g. Numa, who were wise law-makers.

The 19th century Italian thinkers—Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca—developed a more systematic theory about elites (and elitism) and their role in society and politics. Apart from asserting that elites (actually and should) rule, the Italians enriched theory by such notions as “circulation of elites” and “elite renewal”. These notions suggested some mobility and dynamism in elite-ruled societies and had done a lot to counter visions of stagnant elite rule. Some members of the elite can lose their elite status; similarly, some non-elites can join the ranks of the elect.

The contribution of subsequent writers—notably Robert Michels—and the practice of the non-democratic movements of the 20th century—fascism and communism—will usher in richer puzzles. Michels came up with the intriguing theory that asserted—even in avowedly democratic organizations, an elite oligarchy will eventually emerge to rule the same. Fascist movements invariably extolled the Great Leader—Il Duce and Der Fuehrer. And actually-existing socialisms (realsozialismus) had to grapple with the problem of ‘substitutionism’ earlier raised by Leon Trotsky. In Marxist theory, the working class is supposed to be the ruling class in post-capitalist revolutionary societies. In praxis, the working class party, the elite vanguard of the working class, rules in the latter’s behalf. Stalinist practice saw further substitutions: the Central Committee for the Party, the Politburo for the Central Committee, and the General Secretary (Stalin and Stalin-like leaders such as Mao, Castro, Tito, and Kim Il-sung) for the Politburo. All of these substitutions by the elite for a larger body were done in the name of proletarian or socialist democracy.

Even the theorists of pluralism had to deal with the elite conundrum. Contemporaries of Ronald Dahl admitted that the only workable democracies are limited democracies. If all those who were enfranchised by democracy will be politically active, the political system will be unable to process and satisfy all of the inputs satisfactorily. Thus Rousseau’s dream of everybody representing himself in the political arena is a democratic chimera. Or, at best, it may be realizable only in Swiss cantons and New England town hall meetings. The democratic overload supposedly will be more acute in poorer jurisdictions like the Philippines.

Rational choice theorists will further compound the problem. Anthony Downs discussed the paradox of voting in electoral democracies. The paradox stipulates that it was rational for the individual voter not to actually vote because:

- It takes a lot of effort to vote;

- It costs a lot to be fully informed to be able to vote wisely;

- A single vote was not that important; in fact, as more and more people vote, the individual vote loses more and more of its potency.

The Downsian paradox is indeed a paradox since people in significant numbers do vote election after election. These voters cannot be simply dismissed as irrational actors. The subsequent attempts of other rat-choice theorists to solve the paradox are not completely satisfactory. These include notions of socio-psychic rewards, altruistic behavior, and the like. These amendments tended to adulterate the rat-choice model itself. Other rat-choice investigations on the workings of committees (legislative or otherwise) clearly identified the power of certain actors as agenda-setters. All of the efforts from Michels to the rat-choice theorists highlighted the limits of democratic practice and the significant role that elites and political leaders continued and will continue to play in all polities, democratic or otherwise.

All of the puzzles and insights revealed by the above survey of political philosophy and positive theory across the centuries reveal a crucial verity. Despite all the normative preference of many for democratic practice, the technology of rule that had been perfected across time was the rule of the minority. For this reason, principal-agent problems will inevitably arise in democratic polities. The principals—the people, the working class, the citizenry—in modern societies do not have available technologies for majority self-rule. For this reason, they have to appoint agents—to rule in their behalf and in their best interests. The classical problem: who will have custody over the custodians? What will make the agents accountable to the principals? What will prevent agents from lording over their principals?

Locke favored the separation of powers and counseled that the sovereign people will ultimately overthrow an abusive government. However, direct popular action need not have singularly positive effects on democratic political institutions—just take note of the continuing debate over the impact of People Power II on Philippine democratization. While direct popular action may have been recognized as the key principle of our Constitution, the exercise of the people’s will and power can never be fully specified in rules and institutions. This is so since the exercise of direct popular action moves the polity into the unbounded realm of extra-ordinary, non-institutional politics. One must also take note that the outcomes of extra-ordinary political processes are by nature indeterminate. Direct popular action produced the mullah-zerainty in post-Shah Iran and the Taliban in post-Soviet Afghanistan.

Lastly, the exercise of direct popular action are relatively rare historical events and therefore will defy as well as will not require institutionalization. The agents will be curtailed only if some countervailing power from the principals can be exerted on them not only every three or four years, but on a more regular and frequent basis. Of course, the development of this institutional countervailing power will depend on raising the material and cultural assets and capacities of the people. However, the task of institutionalization, of specifying how to exercise this countervailing power on elites—remains a technical imperative.

Reblogged this on bong mendoza's blog.