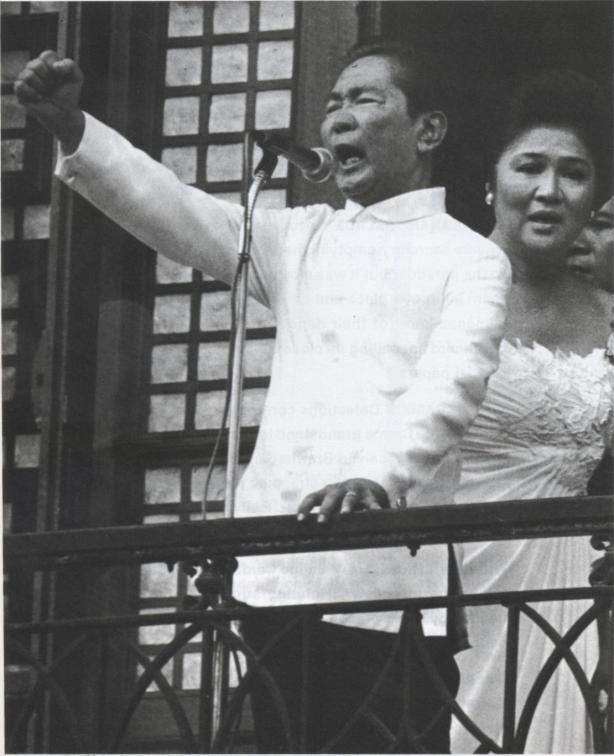

President Fidel V. Ramos

In the previous blog entry, we noted how President Ramos was rebuffed by legislators from his own political party in his attempts to expand the coverage of the value-added tax (VAT) during the first half of his term.

Despite this setback, the imperatives of the tight fiscal situation forced Ramos to propose a more comprehensive tax reform program (CTRP) during the second half of his presidential term. The Comprehensive Tax Reform Program (CTRP) of the Ramos presidency consisted of three laws—Republic Act No. 8184, which restructured the excise tax on petroleum products in support of the Republic Act No. 8180, otherwise known as the Oil Deregulation Law; Republic Act No. 8240, which shifted the taxation of so-called “sin products” from ad valorem to specific; and Republic Act No. 8424, otherwise known as the Tax Reform Act of 1997, which initiated changes in individual and corporate income and in tax administration.[1]

As provided for by the 1987 Philippine Constitution, revenue measures must emanate from the House of Representatives (HOR), the bigger chamber of the country’s legislature. This practice is supposedly consonant with the principle “no taxation without representation”; the HOR members being seen as direct representatives of the citizenry since their mandates are supposedly closer to the grassroots than that of the senators who are elected with the entire nation constituted as an electoral district. In both legislative chambers, the proposed tax measure was handled first by their respective Ways and Means (or Finance) Committees, which may then invite affected parties to offer their views on the proposed measure.

Only after a revenue measure was passed by the House will it be considered by the Senate. There is some controversy over the powers of the Senate in this regard. Some believe that the Senate can only amend the House measure. Others believe that the Senate can overhaul or even throw out the House bill and substitute its own version. These controversies would figure in the passage of the CTRP. After both legislative chambers have passed their versions of a revenue measure, panels from both chambers will constitute a bicameral conference committee (“bicam” for short) to reconcile their differences (if any). The “bicam” will then produce a conference committee report that must be presented and approved by both chambers. Once a proposed revenue measure gets passed by both chambers, it is now considered by the President of the Philippines for approval.

The petroleum tax measure was approved by the House as House Bill 5550, a substitute bill for House Bill 72, which was sponsored by Rep. Marcial C. Punzalan, Jr. (Quezon). HB 5550 was approved by the House in early June 1996. The Senate approved the same measure after a few days and the President signed it into law as RA 8184 on 11 June 1996. The said tax law was a necessary complement to Republic Act No. 8180, otherwise known as the Oil Deregulation Law. RA 8180 also provided for the lowering of tariff duties on crude oil and refined petroleum products from 10% and 20% to 3% and 7%, respectively. In turn, RA 8184 decreed the conversion of the 7% tariff reduction on crude oil together with special oil levies provided for by administrative fiat into a specific tax on refined petroleum products.

Of the three measures comprising the CTRP, this measure was relatively the least controversial. It appears that the policy battles in this issue area were fought during the passage of RA 8180 itself.

The “sin tax” measure was approved by the House as House Bill 7198, in substitution of several House measures including HB 6060 (introduced by House speaker Jose de Venecia himself), the latter being a version drafted by the Department of Finance, which included provisions for income taxation and reforms in tax administration.

Its passage was attended by controversy and considerable attention as the corporate giants affected by the proposed measure—San Miguel Corporation, Asia Brewery Inc. (ABI), Fortune Tobacco Corporation and La Suerte Cigarettes—undertook a massive lobbying and media blitz for and against the measure. San Miguel and La Suerte were in favor of the shift to specific taxation while the companies associated with Lucio Tan (ABI and Fortune) were in favor of retaining the ad valorem ( a percentage of the selling price) tax. However, all of the affected corporations were against indexing the excise tax on cigarettes and beer against inflation.

At one point, the House Committee on Ways and Means tried to satisfy all parties by approving a “whichever-is-higher” formula for beer taxes. This meant that the government could use either the specific tax or the ad valorem tax depending on which tax rate will yield higher revenues. This incurred the Palace’s displeasure since it preferred a specific tax on sin products. HB 7198 was approved by the House (in a 116-11 vote) on 12 September 1996 after it was reconsidered “to allow for perfecting amendments”. The measure was supposed to have been adopted the day earlier. This version appeared to hew close to the Palace’s preferences.

However, many observers including Rep. John Osmeña (Cebu) believed that a rehashed version of the controversial “whichever-is-higher” formula was passed by the House (Jabal, Carlos and Batino 1996). President Ramos then apparently put himself in a ‘Catch-22’ situation when he certified HB 7198 as an urgent measure on 11 September 1996 despite objections from the Department of Finance and some of his cabinet members (Samonte 1996).[2] It took almost two months before the Senate (through a 15-0 vote) could adopt the measure on 7 November 1996, opting for an outright shift to specific taxation (Carlos, Jabal, Santos and Serapio 1996). A bicameral conference committee was formed and met twice (on 13 and 20 November 1996). The sin tax measure was approved and enacted as law by President Ramos on 22 November 1996, just in time for him to claim an important victory before the Association for Asia Pacific Cooperation (APEC) summit meeting in Subic on 24 November of the same year.

In the final version, the specific taxation system was adopted as a rear-guard action by the House to impose a 20% surcharge on foreign cigarette brands was withdrawn during the last ‘bicam’ meeting on the measure (Nuqui, Santos, Carlos & Garcia 1996). In this particular episode, it was quite apparent that the major actors involved compromised to have a rather ‘bad’ sin tax law rather ending up with none at all. It also appears that the country’s creditors and oversight multi-lateral financial institutions (such as the International Monetary Fund) also went along with this compromise.

The passage of the third CTRP component, Republic Act No. 8424, took a longer and more difficult time since a greater number of affected parties were involved. Corporate actors and self-employed individuals lobbied for a lighter tax burden by way of reduced tax rates or exemption privileges while fixed income earners wanted higher levels of allowable deductions and exemptions. While organized industrial and economic interests had minimal collective action concerns in the pursuit of their goals, the otherwise more-difficult-to-organize-and-mobilize fixed income earners found champions in such organizations as the Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC) and in many members of the House who were quite mindful of their chances for re-election in the 1998 general polls.[3]

In addition, proposed reforms on tax administration such as granting the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) Commissioner the authority to examine the bank deposits of suspected tax cheats were opposed by several powerful sectors such as the commercial banks and many of the legislators themselves such that they never got off the ground. These opposition forces also rode on the support of a citizenry wary of the powers of government to pry into the private affairs of individuals—admittedly an attitude developed due to the abuses of the Marcos dictatorship.

The executive department initially opted for a strategy of having the comprehensive tax reform program (CTRP) adopted by the legislature as a single package. It resisted the idea of breaking the package into smaller and more “digestible” bits, fearing that this will result in a watered-down package; that the legislators will adopt the more politically-palatable aspects of the package while passing up on the more controversial, albeit necessary components (Guevara 2003). For this reason, the Department of Finance (DOF) drafted HB 6060 and got House Speaker Jose de Venecia to champion it.

In the end, however, the said package was broken down into smaller measures. HB 7198 dealt with the excise tax on ‘sin’ products while HB 9077 dealt with individual and corporate income taxation and tax administration issues. Nonetheless, HB 6060, sponsored by de Venecia in February 1996, should be regarded as the proper starting point for tracing the legislative history of RA 8424. The emergence of HB 7198 and HB 9077 should be seen as the means through which the House, or more particularly its Committee on Ways and Means headed by Rep. Exequiel B. Javier (Antique) and Rep. Renato Diaz (Nueva Ecija), sought to leave its own mark on tax legislation.

Through HB 9077, the House differed with the Department of Finance (and with the Senate, eventually) on several key issues including the nature of the income taxation system, the minimum corporate income tax (MCIT), the fringe benefit tax, the tax on the interest income of foreign currency deposit unit (FCDU) deposits as well several proposed reforms in tax administration.

Under the global system of income taxation proposed by the House Ways and Means Committee through HB 9077, all types of income derived from whatever source, active or passive, will be taxed under one schedule of progressive tax rates. In a schedular system of income taxation, different types of incomes are taxed at different final rates and are covered by separate tax returns or forms. According to House Ways and Means Committee chairman Javier, the DOF-authored HB 6060 was not adopted by the committee “because it seeks to perpetuate” the schedular system (House TSP, 17 March 1997). However, the House as a whole voted against the committee’s recommendation for a global system of income taxation and opted for a modified schedular system instead.

In HB 6060, the DOF proposed a minimum corporate income tax (MCIT) based on corporate assets. In so doing, the DOF wanted to prevent corporate tax cheats hiding behind a continuous failure to post bottom-line profits to avoid paying income taxes. It believed that a corporation that loses year in and year out “has no business being in business”. House legislators meanwhile had conceptual problems on an “income tax” which was based on corporate assets, a non-income item. Technically speaking, the MCIT was not an income tax and could be a disincentive to domestic and foreign investors for several reasons. For one, the US Internal Revenue Service has ruled the MCIT to be ineligible as tax credit for American firms operating in the Philippines.[4] Furthermore, the MCIT was also seen by the House as a tax that penalizes capital-intensive firms and will discourage corporate expansion. It was also seen as a needless burden for firms who do not make a profit due to normal business reasons or legitimate corporate difficulties.

In its place, the House proposed a five-year net-operating-loss-carry-over (NOLCO) provision for firms.[5] Under this proposal, a firm’s net operating loss from each of the 5 taxable years preceding the current taxable year can be carried over to reduce its income tax payable for the current taxable year. This meant that a firm could declare losses for 5 straight years and avoid paying income taxes. Senator Juan Ponce Enrile countered that tax cheats can still defeat this provision by breaking the 5-year stretch; if a firm declared a profit for a least a year within a 5-year span, it could avoid paying income taxes for four years.

In response to suggestions that the MCIT be based on some income measure such as gross income, DOF officials countered that it was foolhardy to base a minimum income tax on the income declarations of acknowledged tax cheats. The MCIT was precisely based on corporate assets because these items are among the more transparent items in a corporate financial statement (Guevara 2003).

The Senate and the DOF also wanted to tax the fringe benefits of corporate executives and higher-level corporate employees in order to plug loopholes. Under the prevailing setup, corporate executives may opt for lower basic salaries (and correspondingly lower tax liabilities) to receive tax-free or tax-exempt perks such as company-provided or –supported housing, international travel, house help, and educational, medical and dental benefits. All of these perks constituted income-in-kind and should be taxed accordingly. The House opposed the fringe benefits tax based on, among others, the vacuous reasoning that it will make the corporate tax burden heavier. It considered the fringe benefit tax as a tax on corporate expense rather than on individual incomes (see the sponsorship speech of Rep. Javier, HOR-TSP, 17 March 1997).[6]

The House also wanted to maintain the prevailing policy of not taxing income from dividends and FCDU deposits. In contrast, the Senate proposed a 10% final withholding tax on FCDU deposits’ interest income and a graduated tax schedule on dividends (4% in 1998, 8% in 1999, and 10% in 2000). The House reasoned that maintaining the tax-free policy will help prevent the outflow of precious foreign exchange. This argument will gain greater salience in the context of the Asian financial crisis that will hit the country by July 1997. On the other hand, the Senate pushed for these taxes on passive income for reasons of equity. The senators could not see why holders of peso-denominated deposits should pay a 20% final income on interest income while FCDU depositors do not pay any tax.

In all of these issues, the House was supported by the big business sector, as represented by their peak associations. In addition, the House and big business, especially the commercial banks, defeated a provision to relax bank deposit secrecy laws to allow tax authorities to examine bank accounts of suspected tax cheats. House leaders believed that this power is “fraught with potential abuse and is therefore unacceptable” (Javier, HOR-TSP, 17 March 1997). The commercial banks meanwhile alleged that relaxing the bank deposit secrecy law would scare depositors away. On this issue, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas joined the House and the commercial bankers (Garcia, Jabal, Batino and Nuqui 1996) in insisting on bank deposit secrecy.

The House also differed from the Senate and DOF on other income tax issues. It clung to the older practice of taxing foreign-sourced income of citizens and residents while the Senate was in favor of taxing only the income of citizens and residents earned within the national territory. On this issue, House leaders curiously defended their position on grounds of equity: why should income from foreign-based deposits of citizens and residents be exempt from Philippine income taxation when their local peso deposits were not tax-free?

In response, the Senate believed that the new practice would help avoid double taxation of the same income by both countries. The House was also prepared to exempt the foreign-sourced income of overseas Filipino contract workers and seafarers up to a given ceiling.

The House also consistently favored higher levels of allowable deductions from the gross income of individual income taxpayers. While the Senate was amenable to only a P20, 000.00 basic deductions per taxpayer regardless of marital status, the House approved a higher basic exemption of P60, 000.00 per individual. In fact, this issue was one of the most contentious matters that delayed agreement by both chambers. Both chambers however agreed on several key provisions. For one, they agreed to simplify the income tax rate structure by reducing the number of tiers from 10 to six. Both chambers found the DOF-proposed 3-tiered structure (10%-20%-30%) to be too coarse and radical.

HB 9077 was passed by the House with amendments on 8 May 1997 on an overwhelming 156-1 vote. While the House Ways and Means Committee was amenable to fringe benefit taxation, the whole chamber was not. The Senate’s approval came only after almost 5 months of deliberations on 1 September 1997. The Bicameral Conference Committee was convened almost immediately and met for seven times during October 1997. A meeting scheduled for 17 November 1997 was immediately adjourned as Senate panel chairman Juan Ponce Enrile was unable to attend due to his health problems. Enrile’s absence gave opportunities for some House conferees to move for changes in the agreements reached between Enrile and his House counterpart, Rep. Exequiel B. Javier (Arpon, Santos and Duplito 1997). Earlier, both panel chairmen were empowered by their colleagues to meet separately in order to facilitate the resolution of points of disagreement between both legislative chambers. The action of some of the House conferees to change the bicameral committee draft report was opposed by the other members of the Senate panel who insisted that the changes must be approved by Enrile.

Among the changes proposed by the House conferees include raising the allowable tax exemptions for a family of six (consisting of two income earners and 4 dependent children) to P120, 000.00 from P92, 400.00; the retention of the 35% corporate income tax instead of a gradual reduction to 32% from 35% by year 2000; the restoration of tax exemption of gross receipts of thrift banks (which were not subsidiaries of commercial banks) and the 10%-20% tax on capital gains from the sale of unlisted shares of stocks in any domestic corporation (Arpon, Santos and Duplito 1997).

The Bicameral Conference Committee managed to meet a number of times after the aborted November 17 meeting. However, no minutes of these subsequent meetings could be found in the legislative archives. In subsequent meetings, an increase in the level of tax exemptions from P92, 400.00 to P98, 400.00 for a family of six obtained the approval of all of the Senate conferees (Santos and Arpon 1997a). However, some House conferees continued to insist on a P120, 000.00 figure with six of them (Reps. Joker Arroyo, Edcel Lagman, Mar Roxas, Felicito Payumo, Raul del Mar and Ramon Bagatsing, Jr.) dissenting with the bicameral committee report on this account. Three of them (Reps. Gary Teves, Eric Singson and Tajon) did not categorically reject the said report; they signed the report but signified a preference for a higher exemption ranging from P100, 000.00 to P120, 000.00 (Arpon and Santos 1997). With the “yeas” of the Senate conferees, the approval of at least 10 of the 18 House conferees was necessary before the bicameral conference report could be taken up by both chambers. If both panels failed to compromise on the tax exemption level, taxpayers will be back to the prevailing P56, 000.00 figure for a family of six.

It was probably the fear of voter backlash on a much lower tax exemption level that led some of initial dissenters to change their positions as November 1997 waned. Furthermore, more and more of the House conferees that were initially absent when the signatures were being collected also approved the bicameral conference report so that the magic number of 10 signatures was reached. By early December 1997, Reps. Mar Roxas, Tong Payumo and Raul del Mar changed their positions; they explained their change of heart by noting that P98,400.00 was preferable to P56,000.00.

Rep. Mar Roxas even delivered a privilege speech to have his dissenting vote counted as favoring the bicameral report (Arpon 1997). These vote changes were questioned by opposition legislators at the House floor but the bandwagon for the tax measure in the chamber started rolling. On December 8, the Senate approved the bicameral conference report with a 21-0 vote with no abstentions. On the same day, the House approved the same report amidst complaints from some opposition legislators based on some technicalities (Santos and Arpon 1997b).

The tax measure was signed into law by President Ramos on 11 December 1997 and was expected to raise P6 billion in new revenues. Among the revenue earners included in the law were the 7.5% tax on the interest income of FCDU deposits, the gradual hike of dividend taxes to 10% from 6% by year 2000, a 2% minimum corporate income tax based on gross income, an increase in capital gains tax on real property to 6% from 5% for individuals, and a withdrawal of the tax exemption of thrift banks. It could be noted that the MCIT that was approved was now based on gross income and not on gross assets as originally proposed by the Finance department.

[1] Former finance undersecretary Dr. Milwida Guevara argues that in addition to these 3 measures, the Ramos administration’s CTRP also includes Republic Act No. 7716, otherwise known as the expanded value-added tax (EVAT) law (Guevara 2003). Pursuing Guevara’s logic, the tax reform effort of President Ramos should also include the 1993 cigarette tax reform law. However, this same law was the subject of her own doctoral dissertation (Guevara 1995).

[2] Executive Secretary Ruben Torres warned that when he certified a bill as an urgent measure, President Ramos can no longer veto the bill if its final version was not to his liking. Based on Ramos’ marginal notes to HOR speaker Jose de Venecia, his certification was issued on condition the bill was still to be amended by the HOR in accordance with an earlier meeting of the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council (LEDAC) where House leaders committed to adopt the Palace’s version. The Palace’s hopes for a more congenial tax measure therefore depended on the Senate (Samonte 1996; Villegas, Garcia, Jabal & Carlos 1996).

[3] Olson (1965) noted that if the benefits of a proposed policy change are dispersed amongst so many beneficiaries such that the per capita gain is quite minimal, it is relatively more difficult to mobilize political support from these numerous beneficiaries who are unorganized in the first place. In contrast, if the adverse effects of a proposed reform are confined to a fewer number of economic actors, their political opposition to the policy reform is more forthcoming. Furthermore, these economic actors may be organized already and will find it less difficult to mobilize opposition to the reform. For example, while a lowering of the tariff duty on refined sugar will benefit millions of consumers by way of lower prices, it will be easier for the fewer domestic sugar producers to oppose the new tariff measure.

[4] Among the usual terms of a tax treaty between two countries is a provision that income taxes paid by corporations (incorporated in country A but operating in country B) to the tax authorities of country B could be claimed as tax credits by said corporations when they reckon their final income tax obligations to country A’s tax authorities. This provision prevents taxation of the same income by both countries.

[5] The House Ways and Means Committee originally proposed a three-year NOLCO but the House approved a more liberal five-year NOLCO provision.

[6] It could be considered a tax on expense if the fringe benefit tax is levied on corporate employers. As envisioned however by the Senate and the DOF, the fringe benefit tax will be levied on individuals.

14.651170

121.062283