written with Professor Joseph Capuno of the UP School of Economics

Introduction

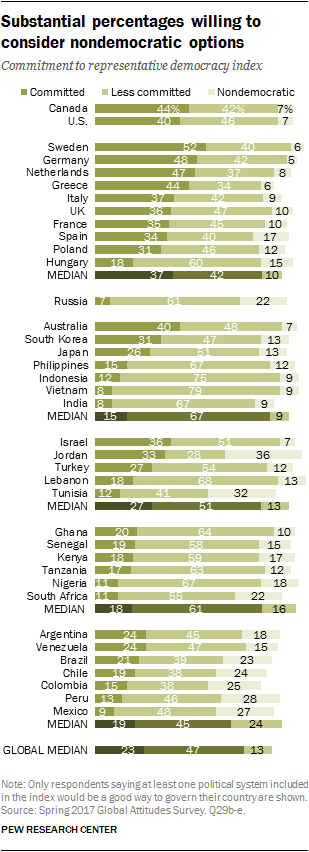

It is the common belief among Filipinos that we are freedom-loving and that we prefer democracy over all other political arrangements. This belief supposedly stems from a long history of rebelliousness against centuries of Spanish, American and Japanese colonialism. In recent years, the preference for democracy and freedom was supposedly affirmed by the struggle against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos from 1972 to 1986 and was consolidated in the national psyche by the EDSA I people power phenomenon. This narrative has been the staple of Filipino pop culture–movies, television serials, radio drama, literature and the like.

American soldiers posing with killed Moro insurgents in the Bud Bajo massacre (Source: https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/moro-insurgents-1906/)

Filipino anti-Japanese guerillas in Mindanao. See http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/981299/more-ph-war-files-not-yet-accessible

However, scholarly opinion differs from this popular perception. Apparently, Filipinos depend on their betters, bow to power, and prefer to be led by a strong and forceful leader, one even willing to brush aside the legal niceties to get things done, and quickly.

There is a strong literature on a ‘big men’ tradition in Southeast Asia and elsewhere (Abinales 2000, Alagappa 1995, Bayart 1993, Bratorry and van de Walle, Brown 1990, Clapham 1982, Ellen 2011, Ileto 2007, Hagesteijn and van de Velde 1996, Kathirithamby-Wells 1986, Kulke 1986, Sahlins 1963, Soenarno 1960, and Wolters 1999). Native terms—orang besar (big men) and orang kaya (rich men) were developed. The American Southeast Asianoligist, Wolters (1999) offered the term ‘men of prowess’. The pioneering Filipino political scientist Remigio Agpalo (1973) asserted that Filipinos respect and fear authority and subscribe to a leader who called the shots. Agpalo indigenized the Platonic ‘medicinal lie’ and formulated his so-called organic-hierarchical paradigm. In Plato’s writings on the role of different men in society, he likened merchants and farmers to the stomach of a person and the soldiers to the arms. For Plato, the rulers of a society correspond to the head or brains. Later, Agpalo will call his paradigm the Pangulo regime (with ulo referring to the head). Even if Agpalo was obviously responding to the strength and charisma of the then newly-installed dictator Marcos, he may not be blamed since some 30 million Filipinos (given a few exceptions such as the Communists and Bangsa Moro insurgents) docilely accepted the Marcosian New Society under the joint leadership and reign of Malakas II (Ferdinand) and Maganda II (Imelda).

Prof. Remigio Agpalo

The play “Fake” by Floy Quintos (directed by Tony Mabesa) reminded one of William Henry Scott’s demolition of the efforts of the antiquarian Juan Marco of Pontevedra, Negros–not far from Bacolod City, not far from the fabled convent of Frayle Pavon–whose manuscripts that referred to the now-discredited Code of Kalantiaw, were earlier considered evidence of ancient pre-colonial civilizations complete with strong leaders and penal codes.

Earlier, Lande (1964) recast the ‘big men’ as the patrons in a super-ordinate relationship with subordinate clients.

Professor Carl Herman Lande

The classic patron-client relationship is that between the landlord and his landless tenant. Related to the ‘big men’ literature is an equally rich one on the role of prominent families and clans in Philippine politics best exemplified by McCoy (1999) and Simbulan (2005). Sidel (1999) meanwhile, highlighted the ubiquity of threats, armed violence, and fraud in the rise and demise of local strong men in Philippine politics.

Immediately after the EDSA 1986 People Power Revolution, an American journalist, James Fallows, (writing in The Atlantic Monthly) referred to the Filipinos’ damaged culture, a play on the lethal mix of almost-400 years in a “Spanish convent” and 40 years in an “American whorehouse or bordello” (For this, please click https://www.theatlantic.com/…/11/a-damaged-culture/505178/ ). He noted the divergence from formal institutions and de facto behavior. Fallows argued that Filipinos from all walks of life are not nationalistic and do not have national pride, unlike its Asian neighbors. he went on to say that this cultural flaw is the main reason why Philippine society will remain in a muddle and economic growth will continue to be middling.

De Dios (2008) revisits the question in his inquiry into the institutional constraints to Philippine economic growth. Among other factors, he also draws attention to the same phenomenon, this time called cognitive dissonance, the divergence between formal institutions and actual practice and that this divergence from rules creates ‘pathologies’ such as corruption, boom-and-bust economic cycles, and political instability, among others. De Dios goes further and explains why the divergence exists: coexistence of foreign and indigenous institutions and corresponding world-views, which look at the same practice differently. For instance, Westerners may call it corruption while Filipinos and other Asians would simply consider it gift-giving or grease (padulas) to facilitate transactions especially between strangers. Westerners insist on impersonal, arms-length relationships while Filipinos are socialized to valorize the family. Former UPSE Dean Prof. Raul Fabella weighed in and talked about the contagion effect: when leaders do not walk their talk, those below them will follow suit and dissonance becomes society-wide; except in Subic and other few places where rules are implemented.

Where lies the truth? With the experts and academics? Or with popular perceptions? This question is interesting and gains traction given the rise of another ‘strong man’ in the person of Rodrigo Roa Duterte as the country’s president (Curato 2017 and Heydarian 2018). Duterte apparently models himself after Ferdinand Marcos, not hiding his admiration for the deceased dictator by having his remains buried in the Libingan ng mga Bayani almost immediately after he was sworn into office in July 2016.

President Rodrigo Duterte (VOA photo)

Or perhaps, it is erroneous to generalize on the political values and attitudes of Filipinos. After all, we are such a diverse lot. It would be interesting to find out if variables which differentiate Filipinos from each other (such as ethnic origin, educational attainment, employment and income status, religious affiliation, etc.) would be associated with differences in views regarding democracy (and related phenomena such as leadership and the role of the military in our political system) and social capital and trust; or whether Filipinos hold common values regardless of the aforementioned differences.

It may be an opportune time to examine the relevant survey data.

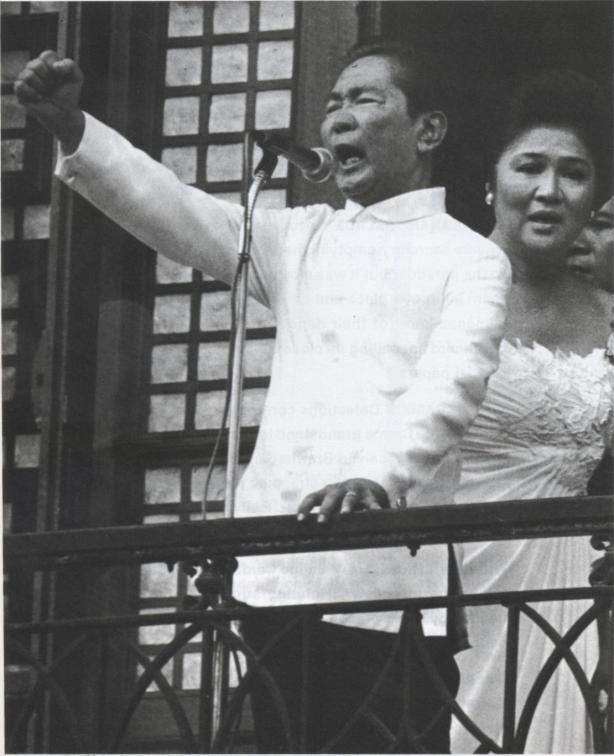

A defiant President Ferdinand Marcos in the morning of February 25, 1986, hours before he was spirited away from the Presidential Palace by USAF helicopters

To be continued…

Bibliography

Abinales, Patricio. 2000. “From orang besar to colonial big man: Datu Piang of Cotabato and the American colonial state. In Lives at the margin: Biography of Filipinos obscure, ordinary and heroic. Ed. Alfred McCoy. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Agpalo, Remigio. 1973. The organic-hierarchical paradigm and politics in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Alagappa, Muhtiah. 1995. Political legitimacy in Southeast Asia: The quest for moral authority. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Bayart, Jean-Francois. 1993. The state in Africa: The politics of the belly. London: Longman.

Bratorry, M. and N. Van de Walle. 1994. “Neopatrimonial regimes and political transition in Africa.” World Politics 46(4): 453-489.

Brown, Paula. 1990. “Big Man, Past and Present: Model, Person, Hero, Legend.” Ethnology 29(2): 97-115.

Clapham, Christopher. 1982. Patronage and Political Power. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Curato, Nicole, ed. 2017. A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on the Early Rodrigo Duterte Presidency. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

De Dios, Noel. 2008. Institutional Constraints on Philippine Growth. UP School of Economics Discussion Paper No. 0806.

Ellen, Roy. Ed. 2011. Modern Crisis and Traditional Strategies: Local Ecological Knowledge in Island Southeast Asia. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books.

Hagesteijn, Renee and Piet van de Velde. 1996. Private politics: A multi-disciplinary approach to “Big-Man” systems. Leyden: Brill.

Heydarian, Richard. 2018. The Rise of Duterte: A Populist Revolt against Elite Democracy. London: Palgrave Pivot.

Ileto, Rey C. 2007. Magindanao, 1860-1888: The career of Datu Utto of Buayan. Manila: Anvil Books.

Kathirithamby-Wells, J. 1986. “Royal Authority and the “Orang Kaya” in the Western Archipelago, circa 1500-1800.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 17(2): 256-267.

Kulke, Hermann. 1986. “The Early and the Imperial Kingdom in Southeast Asian History.” In Southeast Asia in the 9th to the 14th centuries. Ed. David Marr and Anthony Milner. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 1-22.

Lande, Carl. 1964. Leaders, Factions, and Parties: the Structure of Philippine Politics. Monograph No. 6. New Haven: Yale University — Southeast Asia Studies.

McCoy, Alfred. 1999. An Anarchy of Families: Family and State in the Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Sahlins, Marshall. 1963. “Poor Man, Rich Man, Big-Man, Chief: Political Types in Melanesia and Polynesia.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 10(3): 285-303.

Sidel, John. 1999. Capital, Coercion and Crime: Bossism in the Philippines. Stanford University Press.

Simbulan, Dante. 2005. The Modern Principalia: The Historical Evolution of the Philippine Ruling Oligarchy. Quezon City: UP Press.

Soenarno, Radin. 1960. “Malay Nationalism, 1896-1941.” Journal of Southeast Asian History 1(1): 1-28.

Strathern, Andrew. 1980. The rope of moka: Big-men and ceremonial exchange in Mount Hagen, New Guinea. Cambridge University Press.

Windybank, Susan and Mike Manning. 2003. “Papua New Guinea on the Brink.” Issue Analysis No. 30 <http://cis.org.au/images/stories/issue-analysis/ia30.pdf> March 30, 2011.

Wolters, O. W. 1999. History, Culture and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives, rev. ed. Ithaca, New York: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications in cooperation with Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.