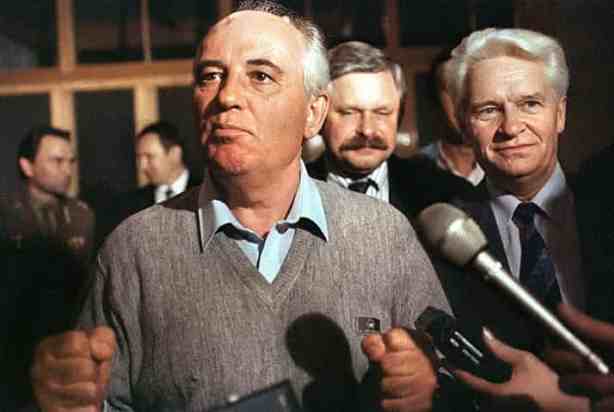

In his prime, Marcos met Mao in Beijing with his family in tow

Before martial law

It must be pointed out that even before he became a dictator, Ferdinand Marcos was already quite adept in making (ill-gotten) money for himself and his family. While he styled himself as a war hero and head of a swashbuckling guerrilla unit (later avowed by the US military as non-existent), Marcos was alleged to have profited handsomely from the buy-and-sell trade during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

In 1968, secret foreign exchange bank accounts were opened in Switzerland with Marcos using the pseudonym “William Saunders” while Imelda posed as “Jane Ryan”. Alongside these secret accounts, several beneficial foundations and shell corporations were also established abroad for their benefit.

Marcos’ transactions with Japanese suppliers and contractors

The irregular relationships between Ferdinand with several Japanese firms and suppliers vying for Japanese official development assistance (ODA)-funded projects in the Philippines are well documented and illustrates vividly how the dictator amassed ill-gotten wealth from a particular source. A general picture of these illicit transactions emerged from several sources including testimony from former Marcos subordinates Baltazar A. Aquino (former Secretary, then Minister, of Public Highways during the Marcos administration, papers supplied by Oscar L. Rodriguez [former undersecretary of the Department (or Ministry) of Public Highways and who was appointed by Ferdinand as implementing officer of the Philippine-Japan Project Loan Assistance Program (PJLAP)], documents (part of the documents and effects seized by the US Customs from the Marcos party as they disembarked at the Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii after their flight from the Philippines after his ouster) pertaining to the Angenit Investment Corporation (Angenit) headed by Marcos crony and former Batasan Pambansa Assemblyman Andres Genito Jr. (Mendoza 1992, In Tsuda and Yokoyama, pp. 10-30).

The Marcos-Japanese relationship started with the Japanese Reparations Program, administered by the Reparations Commission headed by Marcos war buddy and fellow Ilokano General (soon to be Senator) Eulogio Balao. It continued up to the last years of the Marcos dictatorship when the Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund (OECF) became the main conduit of Japanese ODA to the country following the end of the Reparations Program. In general, Japanese ODA funds were to finance specific general infrastructure and development projects in the Philippines. The equipment requirements of these projects were to be purchased from Japanese manufacturers/suppliers in the usual manner of so-called ‘tied aid’. Ostensibly, the Japanese suppliers must compete with each other in an open bidding process wherein the qualified submitting the lowest bid price won the contract. However, Marcos and his associates perfected a system where no Japanese firm could win a contract unless a 15 percent (of the total contract cost) ‘commission’ was handed over. This 15% ‘commission’ would be included in the total contract price to be paid by the Philippine government out of the Japanese ODA monies to the Japanese firms.

Except for a particular instance (i.e., the Cagayan Valley Electrification Project) when they attempted to win contracts without paying any commission to Marcos, the Japanese firms acceded to the ‘commission’ system. All qualified bidders, therefore, knew that they were expected to pay the ‘commission’ if they wanted to bag a contract. They would still compete in the bidding process. One cannot be blamed, however, for thinking that since all were willing players anyway, then contracts were judiciously apportioned to a select group of Japanese contractors in some sort of a queueing system. This meant that if a Japanese contractor did not get a contract for a given project, it could still get one for another project.

The key Marcos aides involved in the operations were General Balao, Secretary Aquino, Undersecretary Rodriguez, and Assemblyman Genito. Balao collected ‘commissions’ on projects financed under the Reparations Program. Most of these projects were administered by Philippine government agencies other than the Department/Ministry of Public Highways. Genito took Balao’s place when the latter suffered a stroke. In a kind of a division of labor, Aquino collected ‘commissions’ on projects administered by the Department/Ministry of Public Highways and financed by the Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund (OECF). Rodriguez, who was accountable only to Marcos, though technically Aquino’s subordinate, took care of the technical function of accepting and evaluating bids and recommending (to Marcos) the award of contracts to specific firms. He could have been in charge of the ‘queueing system’ alluded to earlier.

The Japanese firms that paid regular ‘commissions’ to Marcos through Aquino included Sakai Heavy Industries, Sumitomo Corporation, Toyo Corporation, Nissho-Iwai, and Mitsui & Company. Four representatives—Susumu Makino of Sakai, Yoshiko Kotake and a Mr. Hara of Toyo, and a Mr. Sato of Sumitomo—alternately handed over these payoffs to Aquino in Hongkong.

From September 1988 to November 1989, the Sandiganbayan[1] conducted “perpetuation of testimony proceedings” of an ailing Aquino (who was 78 years old in 1989). The proceedings were done in conjunction with the hearing of several civil suits against Marcos, his family and friends where Aquino was a prosecution witness. Among the major revelations of these proceedings include:

- On several occasions from July 1975 to July 1976, Aquino travelled to Hongkong to receive monies from Japanese representatives, particularly Makino of Sakai. He would then deposit the same amounts into a numbered account (No. 51960) with the Hongkong branch of the Swiss Bank Corporation. As evidence of these deposits, a Swiss Bank Hongkong official named Mr. Barasoni issued deposit receipts in Aquino’s favor. Upon his return to Manila, Aquino would immediately report to the Palace and hand over the same receipts to Marcos. Marcos would in turn accept the receipts silently and store them.

- Aquino testified that Marcos instructed him to keep his Hongkong activities secret and unknown even to Aquino’s wife. In response, Aquino wrote Marcos a letter dated May 25, 1977 promising to keep his mouth shut.

- After General Balao’s death, Marcos expressed some worry that Genito was not giving a proper accounting of ‘commissions’ from the Japanese firms received through Angenit Investment Corporation. Undersecretary Rodriguez was asked to perform an audit and Rodriguez subsequently prepared a ledger of commissions received by Balao and Genito. He found out that Genito was short of one hundred thousand US dollars (US$100000.00). For his part, Genito tried to ask Aquino to withhold the Rodriguez report on his shortcoming from Marcos.

- Kotake of Toyo Corporation wrote Genito to advise Marcos not to use Aquino to collect ‘commissions’ due from the Japanese contractors. Kotake warned of the possibility of scandal (similar to the Lockheed affair that led to the imprisonment of former Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka) considering that Aquino was a government official and was himself in charge of Japanese-funded Philippine infrastructure projects.

___________________________________________________________________________

Note

[1] The Sandiganbayan was a special court created by the Philippine government during the Marcos dictatorship to try graft cases filed against government officials.