Boris Yeltsin (holding a piece of paper) atop a tank in front of the Russian Parliament rallying support against the August 1991 coup

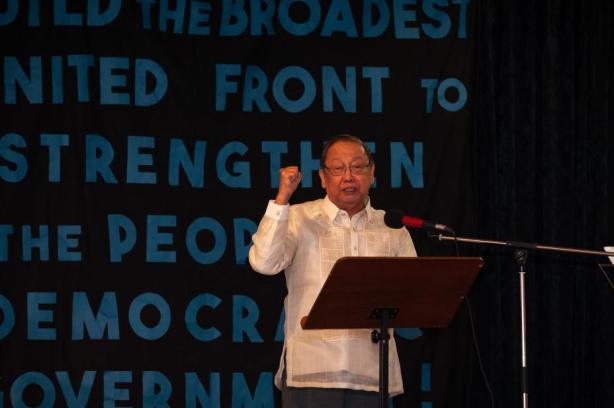

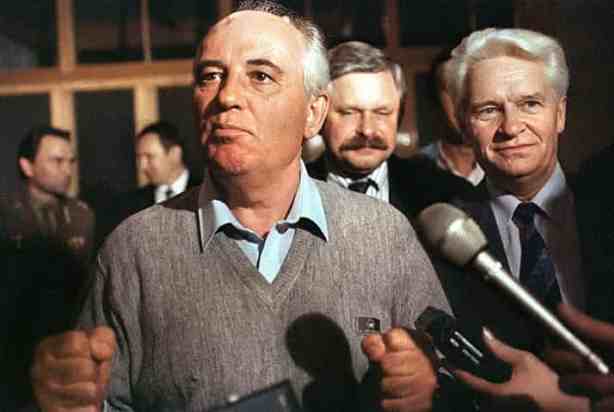

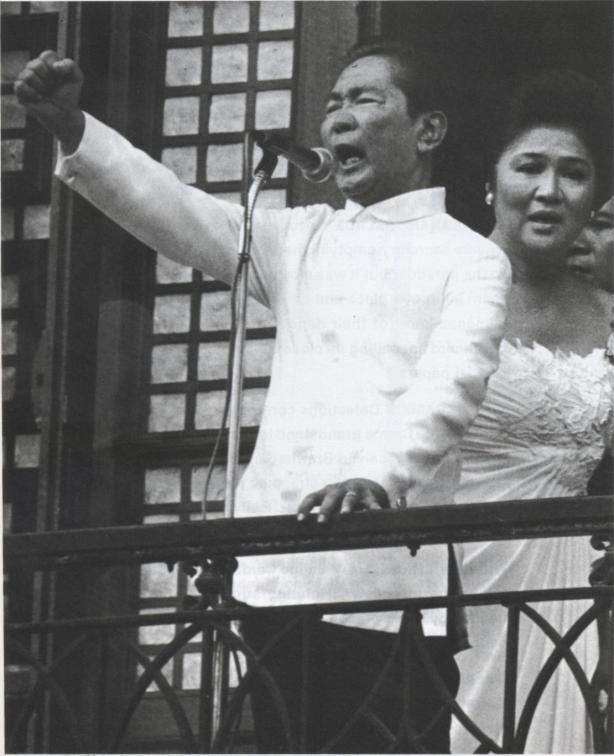

In this paper, we sought to develop three-player game-theoretic models to depict the transition from authoritarianism in both the Soviet Union and the Philippines in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We noted that while the same models apply in both countries, the outcomes of the transitions were dissimilar. In the Soviet Union, the radical transformer (personified by Boris Yeltsin) outmaneuvered both the conservative standpatter (personified by Yegor Ligachev) and the centrist reformer (personified by Mikhail Gorbachev) and presided over the demise of the Soviet state. In the Philippines, meanwhile, the Johnny-come-lately centrist reformer (personified by Cory Aquino) overcame the first-mover advantage of the radical revolutionary (personified by Jose Ma. Sison), who bore the brunt of the struggle against the dictatorship of the conservative standpatter (personified by Ferdinand Marcos).

Mikhail Gorbachev returns to Moscow after coup was crushed

While we may have to discount the obvious differences between the Soviet Union and the Philippines, what key variables may account for the contrasting outcomes in these transitions from authoritarianism? The first one is the international environment (both material and ideational). It could be argued that the prevailing international environment was friendlier to the eventual fall of communism in the Soviet Union but hostile to a communist victory in the Philippines. Ideationally, the Marxist ideology and the communist project have been on the defensive globally and in both locations. Stalinism in the Soviet Union is a blot on Marxism and on the Soviet communist state and party. Stalinist practice had revealed the gap between the humane and progressive promise offered by Marx in his voluminous writings and gave rise to the phenomenon of ‘actually existing socialism’ or realsozialismus. That reformers have been active since the late 1950s in the Soviet Union is a clear indication that realsozialismus either has lost steam after its initial successes or is essentially flawed. The United States, arguably the more powerful state in the Cold War dyad, has not masked its goal of regime change in the Soviet Union and has worked hard, together with its global allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and elsewhere to achieve such an objective. On the other hand, the Sino-Soviet split which divided the international communist movement in the 1960s also weakened the Soviet Union as well as helped discredit Marxist ideology. When the United States normalized relations with the People’s Republic of China in the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had to contend with a de facto Sino-American-Western European anti-Soviet alliance. The Soviet allies in the Warsaw Pact were a collection of weaker powers beset with the same sclerotic economies. In effect, the balance of power and influence during the late 1980s and early 1990s were against the Soviet Union.

Similarly, the United States was likewise hostile to a communist victory in the Philippines, a country which hosts the largest US military bases outside continental United States. While President Ronald Reagan was quite reluctant in ditching his personal friend, Ferdinand Marcos, he was eventually made to see the light by more prescient US officials, especially the US Ambassador and other senior staff members at the US State Department—that Marcos was a liability to the United States, that his continued rule encouraged the growth of the Communist insurgency, and that supporting Cory Aquino and her allies was the best alternative to protect US interests in the Philippines.

The communist insurgency in the Philippines was generally bereft of international allies. Save for a few left-leaning parties and Church-based organizations movements in Western Europe and the United States, the Filipino communists were practically isolated from the rest of the world. China has stopped assisting them after Marcos, following the US’ lead, normalized Philippine-China relations and adopted a one-China policy[1]. The Filipino communists’ association with China and Maoism may also be a reason why the Vietnamese communists ignored them even after their victory in 1975. The CPP could not even forge a strategic alliance with the Bangsa Moro insurgents even if both shared the Marcos dictatorship as a common enemy given the former’s communist ideology. For this reason, the international supporters of the Bangsa Moro insurgent secessionists were either hostile or lukewarm to the Filipino communists. Lacking external assistance, the communist insurgency remained unable to advance beyond guerilla warfare notwithstanding its glowing self-assessments.

A sullen pro-coup soldier atop his tank in Moscow

Another important variable is the domestic balance of power in both countries. In the Philippines, the balance of forces is arguably against the possibility of a communist victory. Through its own decision of boycotting the 1984 parliamentary elections and more importantly, the February 1986 snap presidential elections, the CPP severed its alliance with Cory Aquino’s camp and practically removed itself from the political center stage. The Filipino communists were practically allied with the Marcos dictatorship in this regard since an election boycott objectively helps keep the dictatorship in power. All major anti-Marcos political forces—the US government, the Catholic Church, non-crony big business, military rebels—were hostile to a communist victory and supported the centrist reformers led by Cory Aquino for a non-communist post-Marcos polity.

A defiant dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, rallies his supporters hours before he fled from the presidential palace on February 25, 1986

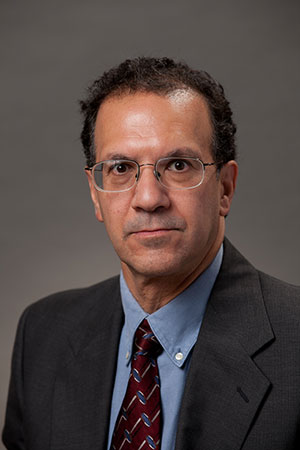

Our understanding of what happened to Gorbachev and the Soviet Union will be facilitated if distinct phases are identified. The Gorbachev period could be divided into four phases: 1985-86, the ‘early’ phase; 1987-1989, the ‘peak’ phase; late 1989-August 1991, the ‘confused’ or ‘retreat’ phase; and August to December 1991, the phase of ‘liquidation and reconstitution’. The early phase represented a ‘groping’ period for Gorbachev as most of the initiatives for economic reform were simply variations of previous programs. What was novel and refreshing in this period was the blossoming of glasnost (openness) and the friendly foreign policy initiatives to the West. The ‘peak’ period was distinguished by moves to effect comprehensive restructuring, especially on the economic, political and ideological fronts. The ‘retreat’ phase saw economic reform getting mired as the CPSU sustained significant political setbacks, opposition to reform got consolidated, and as the nationalities problem boiled over. The failed August 1991 coup marked the transition into the fourth phase, a relatively short one that ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Conservative leader Yegor Ligachev

Changes in the balance of power could be charted through these four phases. In the early phase, none of the three factions—conservative, centrist, and radical—was ascendant. Gorbachev’s faction was clearly dominant during the peak phase. However, Yeltsin’s faction rose in power during the ‘retreat’ phase as Gorbachev got associated with the conservatives especially on the nationalities question. The fourth period saw the final triumph of the Yeltsin faction, the ascendance of the Russian Federation, and the disappearance of the Soviet Union.

The main reason why political forces and factions are personified by political leaders in both transitions from authoritarianism is the importance of a third variable: the quality and political acumen of political leaders. Conservatives in both countries, personified by Yegor Ligachev and Ferdinand Marcos, were discredited, tired, and lacking in political acumen. Ligachev and his colleagues foolishly misread the temper of the times, over-estimated their political strength, and launched a botched coup. Marcos meanwhile also misread his political strength and agreed to hold an unnecessary snap presidential election. He was supposed to serve a six-year term after his ‘election in 1981 and the next regular elections should have been in 1987. In contrast, Cory Aquino benefited from being the widow of the assassinated Benigno S. Aquino, Jr., who in his death was likened to the Philippine national hero Jose Rizal or even Jesus Christ. Neither the dictatorship nor the communist insurgency had an equivalent figure (Mendoza 2009/2011). The Filipino communists, personified by CPP founding chairman Jose Ma. Sison, also misread the political climate and erroneously removed themselves from the political center stage when they boycotted the February 1986 snap elections. Gorbachev meanwhile tarnished his reformist image and lost a lot of his followers when he sided with the conservatives on the nationalities question. He even lobbied hard to get conservative leader Gennady Yanaev named as his vice president (The Economist 1991d). Yeltsin’s opposition to the coup elevated his political stock and enabled him to set Gorbachev aside as the death knell for the Soviet Union played during the last half of 1991.

Cory Aquino

What further insights could be gained from these two transitions from authoritarianism albeit in two most dissimilar countries? First is the banal observation that a three-player political contest will most likely morph into a two-player game for a victor to emerge. Otherwise, the political game will remain unresolved. Second, reforms gain traction if first, they are initiated by factions of the ruling regime and second, if the ruling regime gets divided. In both countries, the desire to end authoritarianism had been articulated by the relatively powerless underclasses and isolated political personalities. Only after the cudgels of reform (and regime change) had been taken over by elite opposition leaders saw the creation and mobilization of a supportive political mass movement to win victory. Of course, as noted earlier, the quality and political acumen of these elite opposition personalities matter.

Communist guerillas in the Philippines

Another insight concerns the non-violent character of both transitions from authoritarianism. The non-violent removal of Ferdinand Marcos in February 1986 through a mass uprising that had started in 1983 was a landmark event both in the Philippines and internationally. It introduced the term ‘people power’ into academic and journalistic discourse and was used as a model for subsequent civil disobedience movements in Asia and the Soviet bloc. The mobilized crowd is thus a key feature in both transitions. The apparent key here was the side-lining of violence-prone political forces in both the Soviet Union and the Philippines. The Soviet conservatives, rebuffed in the constitutional and parliamentary fronts, tried to win the political contest through a coup but were defeated anew ironically through non-violent means. The Filipino communist revolutionaries were meanwhile sidelined by their own strategic error of isolating themselves from the anti-dictatorship movement that chose to fight the dictator through the ballot box and not through guns. In both episodes, millions of aroused and mobilized unarmed civilians tipped the balance of power in favor of the eventual victors. As a consequence, the Soviet Union disappeared and the Marcos dictatorship was ousted.

_______________________________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Books, book chapters and journal articles

Aslund, Anders (1991). “Gorbachev, Perestroyka, and Economic Crisis.” Problems of Communism 40(1-2): 18-41.

Bachrach, Michael (1976). Economics and the Theory of Games. London: Macmillan.

Bonner, Raymond (1987). Waltzing with a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy. New York: New York: Times Books.

Boudreau, Vince (2004). Resisting Dictatorship: Repression and Protest in Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bova, Russell (1991). “Political Dynamics of the Post-Communist Transition: A Comparative Perspective.” World Politics 44(1): 113-138.

Carr, E.H. (1950). A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution 1917-1923, Vol. I. New York: MacMillan.

Ferrer, Ricardo (1990). “A Mathematical Formalization of Marxian Political Economy.” UP School of Economics Seminar Papers.

International Monetary Fund, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and European Bank for Reconstruction (1990). The Economy of the USSR. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

Jones, Gregg (1989). Red Revolution: Inside the Philippines Guerrilla Movement. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

Kagarlitsky, Boris (1990). Farewell Perestroika: A Soviet Chronicle. London: Verso Books.

Kochan, L. and Abraham, R. (1982). The Making of Modern Russia. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Mendoza, Amado Jr. (1992). “The Soviet Reform Process, 1956-1991: From Socialist Renewal to Liquidation.” MIS Thesis, University of the Philippines (ms.).

Mendoza, Amado Jr. (2009). “’People Power’ in the Philippines, 1983–86.” In Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, pp. 179-196. Ed. Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash. Oxford University Press.

Munting, Roger (1982). The Economic Development of the USSR. London: Croon Helm.

Nove, Alec (1982). An Economic History of the U.S.S.R. Penguin/Pelican Books.

Olcott, Martha (1991). “The Soviet (Dis)Union.” Foreign Policy No. 82, pp. 118-136.

Preobrazhensky, Eugen (1980). The Crisis of Soviet Industrialization: Selected Essays. London: MacMillan.

Snyder, Richard (1992). “Explaining Transitions from Neopatrimonial Dictatorships”. Comparative Politics 24 (4): 379–400.

Snyder, Richard (1998). “Paths out of Sultanistic Regimes: Combining Structural and Voluntarist Perspectives”. In H. Chebabi and J. Linz (eds.). Sultanistic Regimes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 49–81.

Thompson, Mark (1995). The Anti-Marcos Struggle: Personalistic Rule and Democratic Transition in the Philippines. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Periodical articles

PDI (1991a). “Union treaty snagged over tax powers.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 28 June 1991.

PDI (1991b). “9 republics back union treaty.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 26 July 1991.

PDI (1991c). “Gorby plan draws party support.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 28 July 1991.

The Economist (1990). “Tsar of a crumbling empire.” 17 March 1990.

The Economist (1991a). “Crime and punishment.” 19 January 1991, pp. 49-51.

The Economist (1991b). “Gorbachev bends to survive.” 27 April 1991.

The Economist (1991c). “And now, Ukraine.” 7 December 1991.

The Economist (1991d). “Superstar without superpolicy.” 5 January 1991.

_____________________________________________________________________

[1] See Mendoza (2009/2011) and Casiple and Mendoza (2015) for further details.