https://usapangecon.com/2018/09/20/mga-dapat-mong-malaman-tungkol-sa-exchange-rate/

Mainam ang pagpapaliwanag ni Ginoong Jefferson Arapoc hinggil sa exchange rate, o yung katumbas na halaga ng pera ng isang bayan sa salapi ng isa pang bayan.

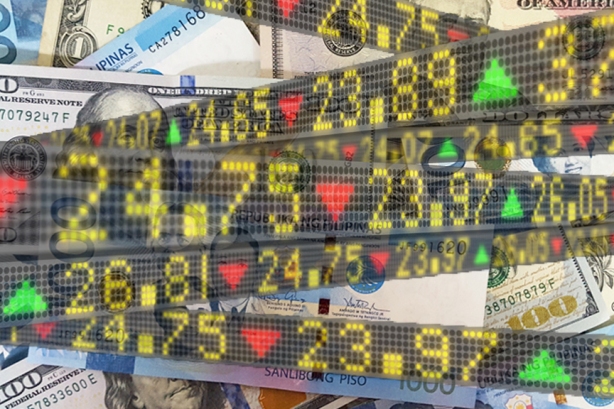

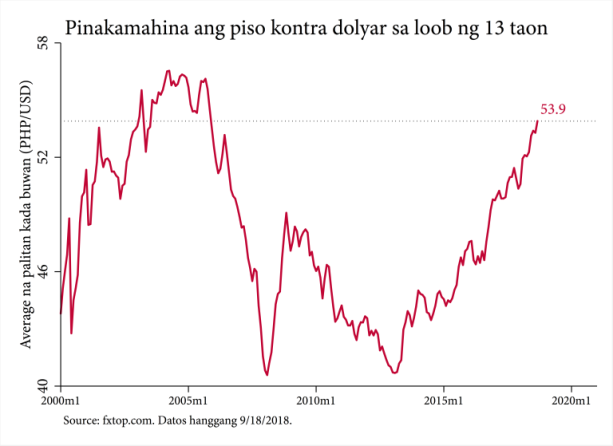

Sa ating mga Pinoy, ang pinakababantayan nating exchange rate ay yung palitan ng ating pera, ang piso, kontra sa dolyar ng Estados Unidos. Sa ngayon ay naglalaro ang palitan na yan sa halagang P54.00 sa isang dolyar.

Tulad ng ating naunang ginawa hinggil sa inflation o yung bilis ng pagpalit ng mga presyo ng mga batayang bilihin, bubusisihin natin ngayon ang exchange rate o yung palitan ng isang salapi, katulad ng piso, sa isa pang salapi, katulad ng dolyar bilang isang usaping pampulitika.

Mag-kabit at mag-kaugnay ang inflation at exchange rate hindi lamang sa larangan ng ekonomiya kundi maging sa larangan ng pulitika.

Magsimula tayo sa pagkilala na ang isang bansa ay nakikipag-kalakalan sa mga banyagang bansa. Una’y dahil ang isang bansa ay nangangailangan ng mga produkto at serbisyo na di nito kayang gawin o kaya’y kulang ang kaya niyang gawin kumpara sa kabuuang pangangailangan ng kanyang ekonomiya.

Pangalawa, nais ng mga lokal na kapitalista na palawakin ang palengke para sa kanilang mga produkto. Hindi sila kuntento na maibenta lamang ang kanilang mga produkto at serbisyo sa loob ng isang bansa. Gusto nilang makabenta sa ibang bansa sapagka’t mangangahulugan ito ng higit ng maraming benta at mas malaking kita’t tubo.

Pangatlo, kailangan din nating maunawaan na kapag bumili tayo ng mga produkto at serbisyo mula sa ibang bansa (yung tinatawag na import), hindi natin maaring gamitin ang ating sariling pera, ang piso, bilang pambayad sa ating mga import. Hindi katanggap-tanggap ang piso na pambayad sa ating mga import. Kailangan nating magbayad sa pamamagitan ng mga katangap-tanggap na salapi tulad ng dolyar, Euro, yen, at pound sterling.

Saan kukunin ng mga Pinoy tulad natin ang mga dolyar at Euro na kailangan natin para pambayad sa ating mga import?

E di sa pagbenta ng sarili nating mga produkto’t serbisyo sa mga banyaga!

Magkakaroon din tayo nga mga dolyar at iba pang mga banyagang salapi mula sa mga dayuhang turista dumadalaw sa ating bayan.

Nagkakaroon din tayo ng dolyar sa pamamagitan ng mga padala ng mga Pinoy na nag-tatrabaho sa ibang bayan (yung tinatawag nating mga OFW).

Kung nagbenta tayo sa mga Amerikano, magkakaroon tayo ng mga dolyar. Kung nagbenta tayo sa mga Europeo, magkakaroon tayo ng mga Euro at yen kapag nagbenta tayo sa mga Hapones.

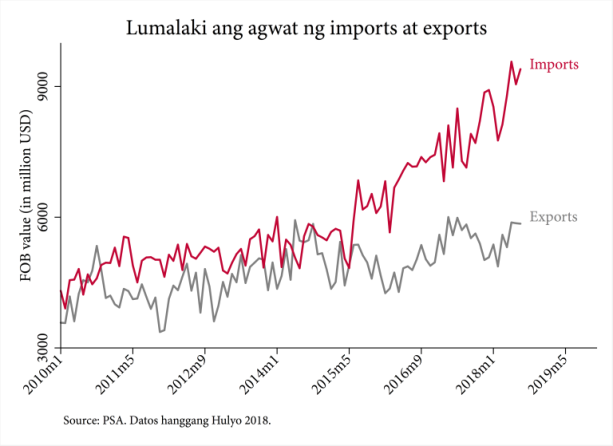

Kaya mahalagang malaman kung mas marami ang kita natin sa pagbenta ng ating mga produkto at serbisyo sa mga banyaga kesa sa ating gastusin sa pagbayad ng ating mga binili o inangkat mula sa mga ibang bayan. Itinuturing na mainam kung mas maraming dolyar na pumasok kesa sa lalabas bilang pambayad sa ating mga import.

Kung kulang ang imbak nating dolyar mula sa benta ng ating produkto sa mga banyaga para pambayad sa ating mga inangkat, kakailanganin nating makakuha ng dagdag dolyar sa ibang paraan tulad ng pangungutang sa mga banyagang pamahalaan at bangko kasama na rin ang mga multilateral tulad ng International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Hindi tiyak na mas marami tayong kikitaing dolyar kesa sa kailangan nating pambayad sa ating mga import. Hindi tiyak o garantisado na makakahiram tayo ng sapat na dolyar para matustusan ang ating mga pangangailangan sa dolyar.

Kung may kakulangan sa kailangang dolyar ang isang ekonomiya, malamang na babagsak ang halaga ng kanyang salapi laban sa dolyar.

Maaring matuwa ang pamilya at kamag-anak ng ating mga OFW dahil mas marami silang makukuhang piso kapag nagpapalit sila ng ipinadalang dolyar.

Kaso, di natatapos dun ang usapin.

Alam natin na ang pagtaas ng halaga ng dolyar laban sa piso ay may masamang epekto sa presyo ng mga batayang bilihin sa loob ng bansa. Tataas tiyak ang presyo ng gasolina at diesel dahil kailangan tayong umangkat nito mula sa ibang bansa, lalo na sa mga bansang nasa Gitnang Silangan tulad ng Saudi Arabia. Alam din natin na ang pagtaas ng presyo ng gasolina at krudo ay magdudulot ng pagtaas ng presyo ng mga batayang bilihin tulad ng bigas at iba pang pagkain, kuryente, tubig, pamasahe, atbp.

Nauna na nating naipaliwanag ang epektong pulitikal ng pagtaas ng presyo ng mga batayang produkto at serbisyo. Maaring basahin ito sa pamamagitan ng pag-click sa sumusunod na link:

https://bongmendoza.wordpress.com/2018/09/20/inflation-usaping-pampulitika/

Liban sa epekto sa presyo, ano pa ang maaring epekto ng pagbabago ng exchange rate sa ating pulitika?

Itutuloy…