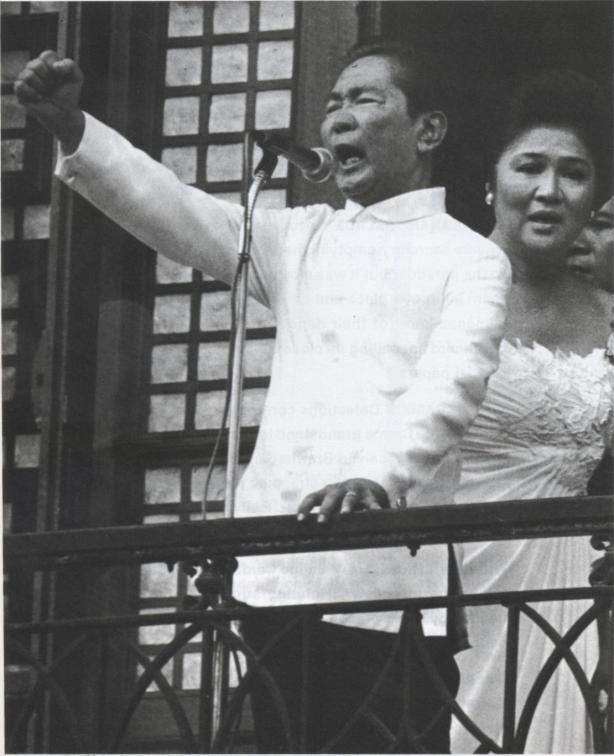

Political contenders in martial law Philippines

The corpse of Benigno Aquino Jr being loaded into a military wagon after his assassination at the Manila International Airport on 21 August 1983

As we did in the earlier parts of this blog series, we now specify the political contenders in martial law Philippines (1972-1986) and the political games they play. We pay special attention to the political contests during the 1980s that ultimately led to the ouster of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos in February 1986 through the unprecedented EDSA People Power Revolution.

Ferdinand Marcos and his cousin, AFP COS General Fabian Ver during the EDSA People Power Revolution

Similar to the Soviet political scene during the Mikhail Gorbachev leadership, there are three key players in martial law Philippines. The regime is personified by the dictator, President Ferdinand Marcos, and is generally considered to be strongest political actor at the time. Arrayed against the Marcos dictatorship were the radical armed insurgents led by the Communist Party of the Philippines (personified by CPP founding chairman Jose Ma. Sison) and the moderate opposition led by the widow Corazon C. Aquino (affectionately called Tita Cory). Tita Cory was the widow of former Senator Benigno Aquino Jr. (affectionately called Ninoy), one of the leaders of the moderate opposition, who was murdered immediately after he deplaned from a flight at the Manila International Airport on 21 August 1983.

Corazon Cojuangco Aquino

The outrage generated by the blatant assassination of Ninoy while under the custody of Marcos’s troops in fact was the impetus that revived the political strength of the moderate opposition. Prior to Ninoy’s murder, the political situation got so polarized between the Marcos dictatorship and the armed communists. It was generally believed that if the dictatorship fell, it will be through a military victory of the communist forces. In fact, many observed that the dictatorship itself was the main recruiter, by way of its abuses, for communist guerillas. Prior to August 1983, therefore, the moderate opposition was a minor political actor and had to be content with a junior partnership with the more muscular left through the latter’s legal mass organizations and alliances.

NPA guerillas in Isabela, Northern Luzon

To be sure, there are other political players in the Philippines during that period like the Catholic Church, business groups, professional associations, trade union federations, and the like. We should never forget to include the US government, represented by its Ambassador and his embassy staff, as a key player. However, each of these forces will inevitably align themselves with each of the three key political contenders in the August 1983-February 1986 end-games.

What were the political objectives of the major political contenders? The obvious political objective of the Marcos dictatorship (and the dictator himself) was to stay in power and stave off the challenges from the two other players. Ferdinand Marcos was believed to be ill since 1982 and had prepared for a successor regime in case of his demise or incapacitation. The armed communists meanwhile hoped to seize state power through armed revolution aka protracted people’s war (PPW). They in fact believed that they are making progress and had reached, by the early 1980s (prior to Ninoy’s assassination) a new stage in their armed struggle: that of an advanced sub-stage in the strategic defensive poised to a strategic stalemate with the dictatorship’s military forces.[1] Prior to Ninoy’s murder, the moderate opposition simply wanted to survive given that much of their ranks were reduced through cooptation, murder, exile, imprisonment and cowardice. However, given the tremendous political stimulus generated by Ninoy assassination, it began to entertain thoughts that it could replace the regime in power through non-armed means.

In the few months after Ninoy’s assassination, the moderate opposition was content to continue playing junior partner to the revolutionary Left in a now more energized anti-dictatorship movement. They joined the communists and their allies in the broad alliance called Justice for Aquino, Justice for All (JAJA). Nonetheless, they began organizing their own forces through such vehicles as the August Twenty One Movement (ATOM), spearheaded by Ninoy’s brother, Agapito ‘Butch’ Aquino. Both political forces were able to mount regular protest actions against the dictatorship for the remainder of 1983.

The dictatorship found itself on the defensive after the Aquino assassination and sought to douse the opposition. It first set up a fact-finding commission headed by the sitting Supreme Court Chief Justice Enrique Fernando. However, the members of this commission resigned after legal challenges to its composition. On October 14, 1983, President Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 1886, creating an independent board of inquiry, called the “Agrava Commission” or “Agrava Board”. The board was composed of former Court of Appeals Justice Corazon J. Agrava as chairwoman, with lawyer Luciano E. Salazar, businessman Dante G. Santos, labor leader Ernesto F. Herrera, and educator Amado C. Dizon as members.

The Agrava Fact-Finding Board convened on November 3, 1983. Before it could start its work President Marcos accused the communists of the killing of Senator Aquino: The decision to eliminate the former Senator, Marcos claimed, was made by none other than the general-secretary of the Communist Party of the Philippines, Rodolfo Salas. He was referring to an earlier claim that Aquino had befriended and subsequently betrayed his communist comrades.

The Agrava Board conducted public hearings and requested testimony from several persons who might shed light on the crimes, including the First Lady, Imelda Marcos, and General Fabian Ver, AFP chief of staff. After a year of investigation – with 20,000 pages of testimony given by 193 witnesses, the Agrava Board submitted two reports to President Marcos – the Majority and Minority Reports. The Minority Report, submitted by Chairman Agrava alone, was submitted on October 23, 1984. It confirmed that the Aquino assassination was a military conspiracy, but it cleared General Ver. Many believed that President Marcos intimidated and pressured the members of the Board to persuade them not to indict Ver, his first cousin and most trusted general. Excluding Chairman Agrava, the majority of the board submitted a separate report – the Majority Report – indicting several members of the AFP including Ver, General Luther Custodio, and General Prospero Olivas, head of Aviation Security Commands (AVSECOM).

Marcos lost so much credibility even prior to the assassination and the Agrava Commission’ reports did not help in any way. In 1985, 25 military personnel, including several generals and colonels, and one civilian were charged for the murders of Benigno Aquino Jr. and Rolando Galman (the alleged assassin who was immediately killed by soldiers also on the international airport tarmac. President Marcos relieved Ver as AFP Chief and appointed his second cousin, General Fidel V. Ramos as acting AFP Chief. The accused were tried by the Sandiganbayan (a special court). After a brief trial, the Sandiganbayan acquitted all the accused on December 2, 1985. Immediately after the decision, Marcos re-instated Ver. The Sandiganbayan ruling and the reinstatement of Ver were widely denounced as a mockery of justice.

The assassination of Ninoy helped caused the Philippine economy to deteriorate even further, and the government plunged further into debt. By the end of 1983, the Philippines was in an economic recession, with the economy contracting by 6.8 percent. The downturn continued in 1984-85 precipitating the worst economic crisis for the Philippines since the Second World War. His assassination shocked and outraged many Filipinos, most of whom had lost confidence in the Marcos administration. The event led to more suspicions about the government, triggering non-cooperation among Filipinos that eventually led to outright civil disobedience that eventually climaxed in the 1986 people power revolution, It also shook the Marcos government, which was by then deteriorating due, in part, to Marcos’ worsening health.

By the end of 1985, the Marcos dictatorship had to contend with a worsening twin political-economic crisis. Marcos took an unprovoked gamble and announced a snap elections scheduled for 7 February 1986 during a televised interview with an American host. The stage was set for an electoral battle between himself and Tita Cory. With their decision to boycott the 1986 snap elections, the communists eliminated themselves from the Philippine political center-stage.

The moderate opposition made further gains during the May 1984 elections to the Batasang Pambansa, the unicameral legislative body formed after the cosmetic lifting of martial law in 1981. Through this electoral process, they were able to rebuild their national organizations in time for the great contest in the 1986 snap elections.

It was indeed wise for the moderate opposition to unite behind a single presidential candidate, Tita Cory, against President Marcos. The veteran, Salvador Laurel, agreed to be Cory’s running mate as the moderate opposition’s candidate for vice president. The communists boycotted the 1984 elections and decided to boycott the 1986 snap elections anew. However, many CPP members especially those deployed in the Greater Manila area and other urban centers of the country felt that boycotting the snap elections was a mistake and that the communists will be seen as being aligned with Marcos. A boycott they opined will only help Marcos stay in power. This disagreement, among others, will trigger the splits within the CPP in the early 1990s.

By boycotting the 1986 snap elections, the communists and their allies eliminated themselves as a key political player. The key political exercise was the 1986 snap presidential elections and the communist-led NPA had no potency whatsoever in affecting the outcome of said election. For a quarter (December 1985-February 1986) therefore, the three-player contest morphed into a polarized two-player game. It was an electoral game, a political process that the communists boycotted. I will argue that even if the communists did not boycott the elections and supported Cory, it would not have been able to play a significant role in the Cory government formed after the ouster of Marcos. The other political actors that aligned eventually behind Cory—the Catholic Church, big business, the US Embassy, and the military rebels–were staunchly anti-communist and will not countenance any CPP participation in her government.

A polarized two-person game produces clearer results in that a winner eventually emerges. This is especially true if the game is an electoral game. Nonetheless, the change wrought in February 1986 did not represent a regular transition from an outgoing government to an incoming government that newly obtained an electoral mandate. Though fraud and massive vote buying, Marcos sought victory at all costs even in the full view of an army of international journalists and foreign government observers. The subservient parliament proceeded to declare him the winner of the February 1986 snap elections. The electoral fraud was so blatant that Tita Cory and her lieutenants in the moderate opposition was able to whip up a substantial civil disobedience campaign after she announced her own victory in the Luneta Park. The dictatorial regime’s weakness will be further revealed by the military mutiny led by Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and his own cousin, General Fidel Ramos.[2]

When the few military mutineers were slowly being cocooned by hundreds of thousands of peaceful anti-Marcos civilians (jointly mobilized by the Catholic Church through the controversial Cardinal Sin, other Christian churches and religious groups, moderate opposition political parties, civic clubs , professional associations as well as by dissenting CPP cadres), the character of the political contest changed overnight. Over a few days, the balance of forces tilted against Marcos until finally he was persuaded by Republican Senator Richard Lugar, a key representative of President Ronald Reagan to give up. Marcos finally left the Palace in the evening of February 25, 1986 aboard USAF helicopters to Clark Air Base in Central Luzon. From thence, he and his entourage (and ill-gotten material assets) were flown to Hickam Air Base, Hawaii. In this unprecedented manner, the Marcos dictatorship passed into the pages of history. [(For a fuller account, please read Mendoza (2009/2011), This book chapter can be downloaded from http://www.academia.com].

________________________________________________________

[1] Influenced by Mao Ze-dong’s military writings, the CPP argued that their protracted people’s war [prosecuted mainly through its New People’s Army (NPA)], had reached a new stage—the advanced sub-stage of the strategic defensive stage—because of its capacity to deploy regular mobile forces of up to battalion-size (300-500 fighters equipped with assault rifles) in so-called tactical offensives (TOs) together with guerilla fighters in many parts of the Philippines, especially in Mindanao. The communists also noted a newly-developed capability to launch crippling people’s strikes (welgang bayan) as additional evidence for reaching that new stage. In Mao’s military theory, a protracted people’s war has three major stages: strategic defensive, strategic stalemate, and strategic offensive. The CPP believed that a few years in advanced sub-stage will enable them to achieve strategic parity with the dictatorship’s military forces.

[2] Ponce Enrile reportedly broke from Marcos since he was competing with the Imelda Marcos-Fabian Ver faction. When he supposedly learned of the Marcosian decree designating Imelda as chair of the successor ruling committee, Ponce Enrile started forming a military faction of his own headed by his protégé, Colonel Gregorio ‘Gringo’ Honasan. This faction was officially camouflaged under the name Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM). The military mutiny was sparked by the discovery by Marcos of a RAM plot to attack the Presidential Palace. Fearing arrest and even death, Ponce Enrile, Fidel Ramos, Honasan, and a few hundred RAM military rebels holed themselves in a a military camp and announced withdrawing their loyalty from Marcos and eventual support for President Cory.

Reference

Mendoza, Amado Jr. (2009/2011). “’People Power’ in the Philippines, 1983-86”. In Civil resistance & power politics: The experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present, pp. 179-196. Eds. Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash. Oxford University Press.