The campaign period for the May 2013 by-elections has started. It is probably the best time to review what we (should or already) know about elections in the Philippines.

- Even if the Philippines is in the tropics, it also has four seasons like temperate countries. It has a dry and a wet season. And there’s the Christmas season–purportedly the longest Christmas celebration in the world. It starts in September and ends in early January of the following year. Last but not least is the election season, which starts in January and ends in the middle of May. Note that the election season almost immediately follows Christmas for a seamless stream of festivities. Formally, elections are held only every three years. However, politicians (incumbents especially) usually behave as if elections will be held tomorrow. So they preen, and they tidy up, and they put their best foot forward, and dispense all kinds of goodies to constituents.

- There are only two kinds of politicians in Philippine elections: the winners and the cheated. Instead of conceding gracefully, the default behaviour of losing candidate is to claim the occurrence of fraud in favour of the winning candidate.

- Even if the Philippines is the oldest democracy in Asia, it took more than a century to modernize the way we vote and count votes. Younger Asian democracies (with larger populations) like India had started using electronic voting machines since 1999. In contrast, the Philippines adopted similar machines on a nation-wide basis only in 2010. In both countries, though, the credibility of the voting machines rests on an independent verification system designed to allow voters verify that their votes were cast correctly, to detect possible election fraud or malfunction, and to provide a means to audit the stored electronic results. Since every election in the Philippines is governed by a specific law, the continued use of voting machines is not assured.

- The Philippine Constitution provides for a multi-party system, which is actually more fit for a parliamentary system. While multiple parties exist in name, most of them are mere vehicles for electoral bids of key politicians. There is no prohibition on party switching and voters do not penalize politicians who switch

parties. For example, the senatorial slate of President Benigno Aquino is composed of candidates from several political parties. The opposition line-up is similarly constituted by politicians from different parties. What makes the situation rather absurd is the

adoption by the opposing coalitions of three guest candidates. It is an indication of the bankruptcy and lack of imagination on both sides. There is surely no lack of suitable candidates on both camps but they decided instead to guest ‘sure-win’ candidates. In the past week, so-called guest candidates chose to campaign with the administration candidates. This prompted threats from the opposition coalition that it will no longer carry said guest candidates followed by inane

ripostes from some of the ‘guests’ that their loyalty is to the Filipino people and not to any political coalition.

- At the end of an election (general or otherwise), political alignments will either be with or against the incumbent administration. There is no rule prohibiting those who styled themselves as opposition candidates and won to join the pro-administration coalition after the elections. The move is explained as a way to ensure funds for district projects, the idea being the President is more inclined to approve projects if they were proposed by political allies rather by political opponents. Sometimes, it does not work in such a neat way. Presidents may court the critical votes of opposition politicians by providing pork barrel allocations and other forms of patronage.

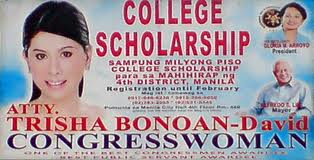

- The discussion above highlights the difference between candidate-centered vs. party-centered electoral systems. In party-centred polities, political parties choose their candidates through primaries, party conventions and caucuses. In these polities, party discipline prevails; party members follow the party (voting) line in legislative bodies. It is unthinkable for politicians to switch parties like butterflies flitting from a flower to another. In sum, what is important is the political party as a ‘brand’. It stands for something–an ideology, a political program–and its leaders and members are secondary. Votes are cast for a politician because he is strongly associated with a party ‘brand’. In contrast, parties are not strong ‘brands’ in candidate-centered systems. Candidates are the ‘brands’ and political parties are just extraneous packaging or wrappings that may be changed in the next election. The candidate does not need an ideology or a political program. Rather, he must have a reputation of performance–of providing divisible favors to constituents, supporters, and financiers such as hand-outs, jobs, infrastructure projects, and preferential treatment by government such as exemptions and special credits. He then claims that these ‘public goods’ were made possible by his ‘private performance’. Thus, the ubiquitous presence of ‘Epal[1] tarps’ in all corners of archipelago make sense.

- In candidate-centered polities like the Philippines, the differences between legislators and local chief executives are blurred. Voters and politicians alike do not consider legislation as the primary work of legislators. If a legislator behaved as a pure legislator and concentrated on making laws, he will most likely not be re-elected. Voters will see him as a useless politician since he did not ‘bring home the bacon’. The legislator must behave like local chief executives (LCEs), as provincial governors, city and town mayors, and even barangay captains, who must deliver divisible goods. For this reason, among others, legislators and LCEs had seen it fit to play a game of electoral musical chairs especially since the enactment of the Local Government Code (LGC) in 1991. Through the 1991 LGC, funds available to LCEs of some local government units (LGUs) became more substantial than those of congressional district representatives. However, a better explanation for this behavior is the term-limit rule. Representatives and LCEs can only serve for three consecutive terms of three years each. The ability to run for other electoral posts helps politicians with expiring terms to maintain their hold on political power.

- The other way around term-limits is to field relatives (wife, husband, son, daughter, etc.) for the soon-to-be vacated post(s). This could just be a bench-warming strategy; the relative keeps the post for a three-year term until the principal is eligible once more to run for the post. However, it could also be an expansionist strategy. The ‘bench-warmer’ had gained valuable experience and exposure; these assets could be parlayed into another electoral post. These circumstances can explain the origins of political dynasties in the Philippines. Let’s recall the case of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. Arroyo hunkered into a survival strategy after her electoral mandate was put

into serious question after the 2005 ‘Hello Garci’ scandal. The strategy apparently covered the post-presidency period and Arroyo ran for a congressional seat in her home province to acquire a modicum of immunity. During her incumbency as President, that same seat was occupied by one of her sons. To accommodate her, the son did not contest the same seat but chose to run for another post instead. The filial ties between mother and son were key to this unprecedented post-presidential survival strategy.

- The Philippine Constitution explicitly prohibits political dynasties. However, the same constitutional provision is not self-executory and requires that an enabling law must be passed. However, all attempts to pass such a law have failed so far, and understandably so since most legislators are members of what could be rightly called political dynasties. The current by-elections can lead to the consolidation of several political dynasties associated with the biggest and brightest names in Philippine politics–Aquino, Angara, Enrile, Cojuangco, Escudero, Binay, etc. The political dynasty issue is rather a complicated one. Proponents of banning or controlling political dynasties argue that it will strengthen Philippine democracy by broadening choice of candidates and removing the undue advantages of dynasties (wealth, experience, exposure, and name recall, among others). Those who would advise caution think an anti-dynasty law is actually an unconstitutional provision. It violates the equal treatment clause of the Constitution. Why should a son or daughter or a brother or a grandson or an uncle be prohibited from contesting an electoral post because a relative is in power? What would justify discriminatory treatment?

- One thing that political dynasties have going for them is that they are better able to handle the ever-rising costs of elections. Key considerations are population growth–the growth of the voting population–and the rather fixed length of the electoral campaign period. In the past, candidates (especially those for national posts) thought it was adequate to rely on hand-shaking, posters, flyers, city-hopping, and miting-de-avance to win. However, the increased number of voters and the fixed

campaign period forced candidates to use television and radio as the primary campaign tools. Not that the mass media corporations are complaining. They are in fact so happy since a previous ban on electronic campaigning was lifted. The increased prominence of electronic media in Philippine elections raises serious questions regarding election campaign finance and electronic campaigning. If TV and radio presence is a function of a candidate’s money, if TV and radio presence enhances a candidate’s name recall and chances of winning, what rules are being implemented regarding these activities? Are they adequate? What reforms are needed?

This is not an exhaustive list; it could be expanded to 50 things about Philippine elections. Perhaps we can end with the question: is it more fun with Philippine elections? The response will be mixed. We do not a have a porn star-member of the Italian parliament who delivers her speeches with a breast exposed. We do not have brawling

parliamentarians as in Taiwan and South Korea. On the other hand, our elections are fun! We love our elections! Elections are fiestas, extravaganzas, spectator sports, boxing bouts, and cockfights all rolled into one. There are movie stars, starlets, stand-up comics, and dance troupes galore. And there’s food and drink. And cash gifts! Reportage on elections reflect these metaphors. Now you know why a lot of Filipinos want elections to happen annually rather than every three years.